By Claire Viadro PhD

To residents of wealthy nations, rickets sounds like an antiquated affliction, conjuring up images of the malnourished youngsters who populate Dickens novels. But while it is true that present-day Europe and North America are far from the situation that prevailed in the early 20th century—when rickets affected up to 80% of children—the past several decades have seen a resurgence of rickets that has researchers in countries like the United States, Canada, and Britain worried. Rickets also persists as a major health problem in many less affluent countries.

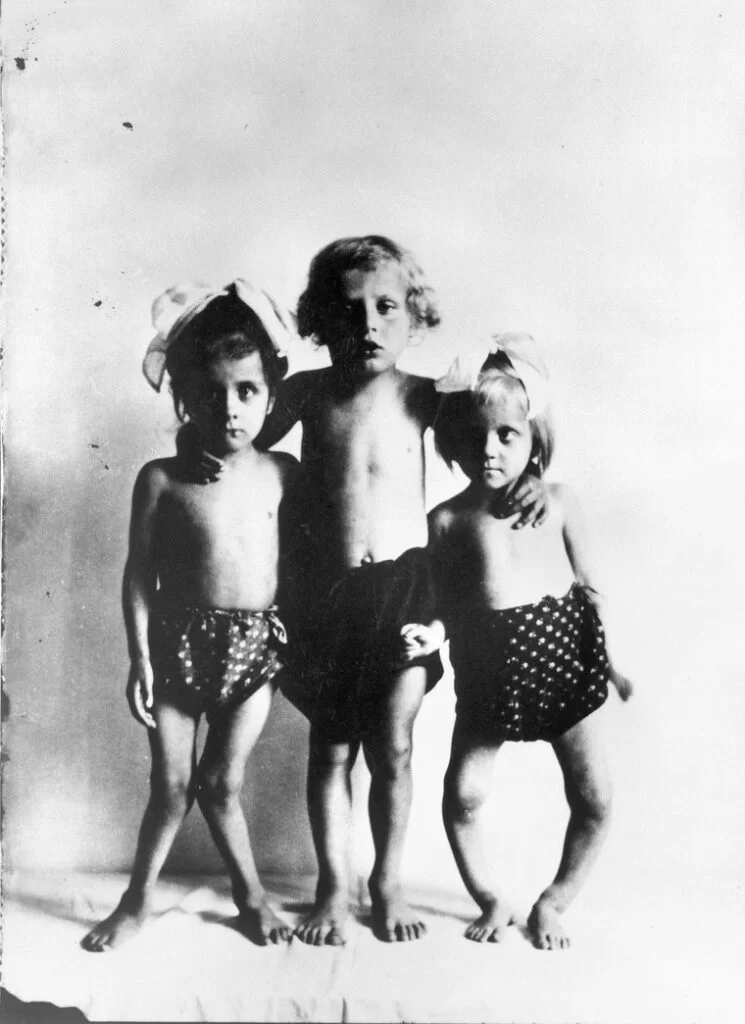

Rickets causes bone deformities—think bowlegs and knock-knees—as well as stunting growth, causing pain and muscle spasms, facilitating the easy fracture of bones, and delaying motor development. Scoliosis, a spinal deformity affecting an estimated four million Americans, can also be a feature of rickets, along with malformations of the cranium or pelvis.

Medical writers documented conditions featuring “bony deformities” as early as the 1st century AD. However, it was not until 17th-century England that the first in-depth description of rickets emerged. Even then, the causes of rickets remained “elusive” until the 20th century. Now, rickets is recognized as a primarily nutritional condition resulting from prolonged vitamin D deficiency or “relative deficiencies of calcium and vitamin D [that] interact with genetic and/or environmental factors.” Even in the absence of overt rickets, vitamin D deficiency “can prevent children from reaching their genetically programmed height and peak bone mass.” Rickets is also linked to conditions such as celiac disease and ulcerative colitis, which interfere with vitamin D absorption and activation.

Cod liver oil and sunlight: the historical response to rickets

Cod liver oil “has been considered…to be critically important for bone health” for at least three centuries, building on the fish oil’s ancient track record of health benefits. And well before the discovery of vitamin D, Europeans in the early 1800s were documenting cod liver oil’s use as a remedy against rickets.

By the late 1800s, some were also prescribing systematic sunbathing for the prevention and treatment of rickets, appreciating the “life-giving properties of the sun” documented in the world’s earliest cave paintings—natural gifts severely challenged by the pollution and lifestyle changes ushered in with the Industrial Revolution. Modern researchers suggest that “More than 90% of the vitamin D requirement for most people comes from casual exposure to sunlight.”

In the early 1900s, researchers showed that feeding cod liver oil to animals with rickets “induced a uniform pattern of healing”—whether in lion cubs, puppies, or rats. This observation led directly to the discovery and naming of vitamin D and to the marketing of cod liver oil as “bottled sunshine.” These breakthroughs in turn paved the way in the 1920s and 1930s for cod liver oil and sunlight to become preferred and widely used rickets remedies, even promoted by the United States Children’s Bureau, along with life insurance companies and state and local health agencies. The Bureau distributed a pamphlet titled “Sunlight for Babies” as well as an infant care booklet with tips for the routine administration of cod liver oil.

Around the same time, however, the burgeoning food industry was successfully putting forth a different solution: vitamin D fortification of commercial milk. Although the gung-ho addition of synthetic vitamin D to milk and other dairy products that continues to this day is given most of the credit for the near-eradication of rickets—with cod liver oil’s role largely ignored—few mention the problems caused by too much synthetic D. Post-WWII Europe banned vitamin D fortification of dairy products after observing that American infants and children who consumed fortified milk were “overdosing” on artificial vitamin D.

Modern-day vitamin D deficiencies

National studies conservatively estimate that 18% of Americans over one year of age are at risk of vitamin D “inadequacy” and another 5% are at risk of deficiency—while others have pronounced vitamin D deficiency an “epidemic for all age groups.” In Europe, studies propose that anywhere from 20% to 60% of Europeans are deficient. Similar studies elsewhere have prompted researchers to describe vitamin D deficiency as a worldwide health problem. These studies, along with the rising incidence of rickets and other conditions associated with vitamin D deficiency, have persuaded many clinicians to recommend across-the-board vitamin D3 supplementation, despite growing awareness that this approach may not be evidence-based.

A number of reasons have been put forth to explain rampant vitamin D deficiency and to justify the reliance on supplements. The first has to do with the relatively limited number of naturally vitamin-D-rich foods, which, besides cod liver oil, include pastured egg yolks, fatty fish, and (to a lesser extent) organ meats and pastured lard. Unfortunately, most modern consumers do not or will not eat these foods. A second explanation concerns modern populations’ inadequate sun exposure, whether due to indoor lifestyles and fear of the sun, overuse of sunscreen, or phenomena such as reduced sunshine duration and increased cloud cover. Additional risk factors for vitamin D deficiency (and, therefore, rickets) include dark-skinned ethnicity, residence in northern latitudes, certain medications, and chronic kidney disease.

Some research suggests that exclusive breastfeeding can be a risk factor for the infant when the mother is vitamin-D-deficient. Vitamin D adequacy in the mother is also vitally important during pregnancy, determining “fetal skeletal development, tooth enamel formation, and perhaps general fetal growth and development.”

To counter the resurgence of rickets, how about a resurgence of cod liver oil?

In 2014, a scornful report by the Philadelphia Inquirer suggested that though “generations of youngsters” had been dosed with “foul-tasting and foul-smelling” cod liver oil to prevent rickets, the advent of vitamin-D-fortified milk had rendered this practice obsolete. However, the Inquirer was wrong to equate synthetic, stand-alone vitamin D with cod liver oil produced using traditional, time-honored methods that preserve the powerhouse food’s full array of nutrients. Dr. Weston A. Price and other researchers of his generation understood the difference, conducting experiments showing that administering vitamin D in isolation produced harmful effects not seen with the administration of cod liver oil. Then and now, those familiar with high-quality cod liver oil know through direct experience that vitamin D is most effective when it is allowed to work synergistically with vitamin A and all of cod liver oil’s other valuable constituents.

Comments are closed for this article!