The milk that brothers Kelly and Kirk Bruns of Bloomfield squeeze from their dairy cows is less than what the Bruns cows used to produce. They once co-owned the top-producing, registered Jersey herd in the state, with a rolling herd average of more than 19,000 pounds of milk per lactation.

“But the cows owned us,” says Kirk Bruns. “Between the feeding and scooping manure from the free-stall barn and milking and heat detecting and recordkeeping and embryo transfer, it was very time consuming. And we wrote a lot of checks.”

Since the Bruns brothers sold their registered Jerseys milk cows and split their operation into two grass-based dairy operations with the heifers they’d reared and a bunch of Jersey crossbreds,”It’s all gotten pretty streamlined.” Kirk says.

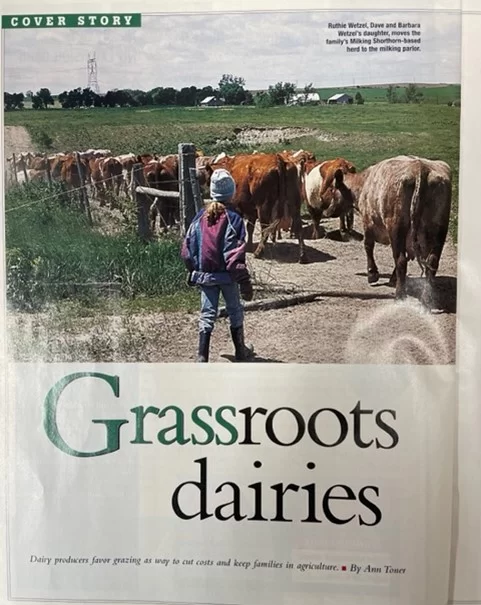

Dave and Barbara Wetzel of Page and their four daughters harvest the grass on their farm with dairy cows, too. “We don’t work for the cows. The cows work for us,” says Wetzel, a Twin Cities native who moved to northeast Nebraska with his family to start the dairy about

a year ago.

The Bruns families and the Wetzels have seasonal dairies. They calve and begin milking as soon as the weather thaws and the grass greens up in the spring. They quit milking and dry their cows off in

the fall when it gets too cold to milk and the snow starts to fly.

They calculate their income and costs by the acre, rather than the return per hundredweight of milk production. They emphasize grass management and keeping their facility costs down. They don’t feed grain or lots of expensive supplements to their cows.

Kelly Bruns says it used to cost $3 to $4 per day per cow to maintain their cow herd. Now they figure their returns by the acre. “The first rotation through the pastures we earned $35 per acre (from the milk produced); the second rotation (with more grass, and more milk from the cows) it was $156 per acre.”

Kelly Bruns has about $35.000 invested in his milking facilities. Dave Wetzel built his for $25,000.

Both had some additional expenses for fencing supplies.

The Wetzels have a small pit-style parlor in a hoop building they’ve built on their farmstead. They bought used milking equipment and a used bulk tank.

The Wetzels have both pivot-irrigated and nonirrigated pastures. They rotate their Milking Shorthorn-based cattle to a new grazing cell nearly every day. They milk every 16 hours.

Kelly Bruns has mostly dryland pasture available. He located his New Zealand-style milking parlor (a roof, a north wall, a milking pit and an enclosed area for the refrigerated bulk tank) in the middle of his pasture to minimize walking for his Jersey- based herd. He milks every 12 hours.

Kirk Bruns is in the process of converting to a grass-based dairy. He grazes his cattle but runs through the old milking parlor the brothers used to share.

The brothers split their dairy efforts and went to grass-based dairying because the cost of expanding conventional dairy facilities to milk more cows was too costly. By grazing instead of confinement

feeding, they can inexpensively expand their cow herds to as many animals as their grass can support.

The Bruns brothers say the conventional expansion would have been prohibitive in today’s farm economic climate. “And we wanted to bring our wives home from jobs in town, and avoid having our kids

raised by babysitters.”

Kelly Bruns and his wife, Cindy, have a son, Cole, 2; and Kelly has a daughter, Kali May, 16, from a previous marriage. Kirk and his wife, Kristi, are the parents of Kara, 4, and Paige, 2.

David Wetzel, a former steel worker, and Barbara Wetzel, a former accountant, bought their farm in order to work together and see their daughters (Ruthie, 9; Claire, 7; Addie, 3; and Carlie, 10 months) grow up around them. Grass-based dairying seemed like a way to do that without a lot of investment in ag machinery or facilities.

“I’ve always been a workaholic. And I decided I’d rather be working at home with my family around me,” Wetzel says. With all he’s had to learn about grass management and the dairy business, he’s

had plenty of work to keep him happy.

The Brunses and the Wetzels sell their milk to two of the area’s dairy processing giants. But they would all like to niche market their milk or other dairy products to certain segment of consumers who perceive superior nutritional and health properties to milk form a

grass-based source.

State dairy regulations allow dairies to sell raw milk from their farm if customers bring their own containers to the farm, and the diary producers warn them that unless they pasteurize it, they will be drinking raw, untreated product.

But the dairies’ distance from a large population center limits the number of people likely to appear, jugs in hand. And their relatively small size and differing philosophies about how their grass-produced milk could be best marketed could limit a joint effort – unless more grass-based dairies spring up in the area.

“I think this kind of dairy could just about be blue-printed and taken to a banker,” says Kelly Bruns. I think it’s a viable alternative for a young farmer just getting started farming.” If farmers have a milking facility, grass and cows, other requirements are quite modest.

“In my opinion,” Wetzel says, “Nebraska could be a wonderful state for grass-based dairies. You’ve got the land values and the taxes, and the water is a tremendous resource.”

Ann Toner. “Grassroots Dairies.” Nebraska Farmer, July 2001

Comments are closed for this article!