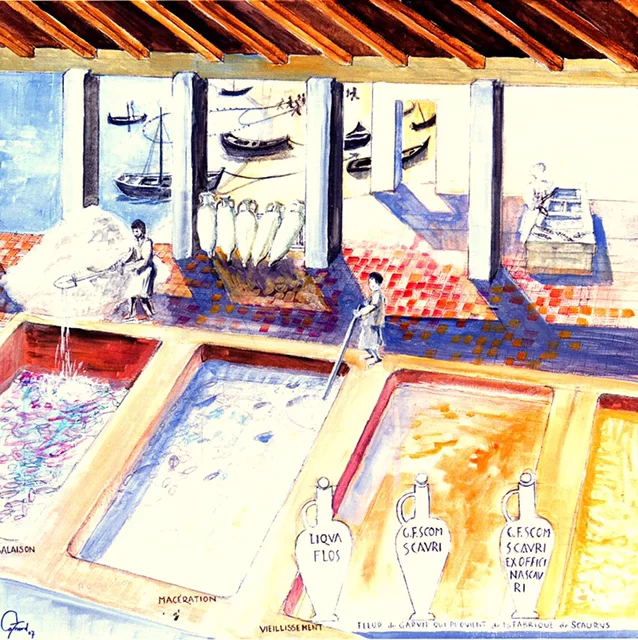

An artist’s impression of the process of making liquamen fish sauce.

Last Updated July 24, 2019

Many people are familiar with the idea that the ancient Romans used fish sauces in their cuisine but not many people realise that the most valued and expensive form of fish sauce was made from, what was perceived by the Romans themselves, as rotten or fermented fish viscera. This special sauce, known as garum, was valued by the elite but it was also used in ancient medicine. Why on earth would anyone ferment fish viscera?

What could possibly be beneficial or desirable in such a practice? It is a very interesting question and one I have spent many years trying to understand. I will share with you my thoughts and ideas on this issue in the hope that it can illuminate the related issue of fermenting cod liver. I will look at the possibility that a form of fermented fish oil would have been familiar to fish sauce manufacturers and therefore possibly also familiar to ancient Greek and Roman doctors. The traditional date for the introduction of the processing of fish liver oils is Viking c. 900 AD. Documented evidence is even later so we are unable to do more than speculate from the complex disparate pieces of evidence both literary, archaeological and empirical.

Ancient Fish Sauces

Ancient coastal societies of the Mediterranean and Aegean relied heavily on fish. In 4th century BC Sicily, the larger species were consumed by an elite who wrote the first gastronomic literature telling us how much they valued the fresh mullet, bream, tuna and shark and numerous other species at their banquets. The first ancient fish sauce that we read about was an unfermented brine derived from the long term storage of salted fish, particularly tuna, and this was initially a valued sauce used at elite banquets as a salty dip.

The rest of the population of the Greek Islands and Italian coastal regions had to be content with smaller species such as sardine and anchovy and juvenile forms of bream and mullet. Once caught, either by one man with a small net or vast seine nets pulled onto the beach, these smaller fish often under 20 cm, and as small as 5 cm, begin to decay within hours in the heat of the day. You either ate them then and there or preserved them with salt using traditional skills and knowledge of preserving that undoubtedly went back thousands of years. Archaeologists have found large dumps of fish bones that must be a residue of a form of fish sauce in many parts of the Greek Islands, from as early as the 2nd millennium BC. The tiny ones can be cooked and eaten without gutting on the spot – we have all eaten whitebait – but the larger size would need to be processed differently if the final product was going to be safe to eat. To gut or not to gut, that is the question? It was simply impractical to individually gut the vast quantities that they caught and it seems that they developed a style of preserving that involved fermenting using relatively low salt, which in essence is allowing lactic acid producing bacteria (LAB) to thrive and generate acid which kills the nastiest bacteria. They clearly didn’t understand this but long tradition provided empirical knowledge of the best way to do it. We have to make a guess as to the process they used. It is not clear whether a solid or sauce product was the first process to be used. A traditional technique which was still being used in Cornwall as late as the1950’s involved the whole fish being piled up into a mound in layers of fish and salt. The salt would draw out the water content of the fish, which would drain away, and also dehydrate the flesh and internal organs.

Under these conditions pathogenic bacteria cannot grow – they need moisture – but lactic acid producing bacteria rather like a little salt and they thrive too. The fish are being fermented and salted in one and the result is entirely safe, and for those brought up on the taste, quite delicious! It’s pungent and slightly ‘off’ in the way that some of the finest French cheeses have more than a whiff of the farmyard about them! It may be guessed that most food at this time was pretty dull and any product that could offer this umami punch of flavour was desirable and became the taste experience that people sought.

This traditional Cornish technique may also have been applied using wooden vessels such as barrels, and wooden buckets with holes in them. The brine would run away through holes or the barrel slats. The origin of the ancient Mediterranean liquid fish sauce, rather than a semi dried and compressed fish, seem to me to be the result of a happy mistake. One day the brine did not drain away as it should. Maybe the staves of the barrel were too tight or the holes of the wooden vessel got bunged up. It was then left in a corner and forgotten and magic occurred? Over, what is later determined to be about 4 months, the fish turned to a liquid and produced a deep dark sauce full of umami flavour enhancing qualities that we all know and love today.

This sauce is not technically fermented as it is the enzymes in the intestinal organs of the fish that breakdown the fish muscle tissue into particles which subsequently under autolysis convert the protein into a dissolvable form. It is clear that some LAB play a part too though this depends on the levels of salt used and how it is processed. These sauces were very nutritious and as with the sauces of Southeast Asia today, may have served as the main source of protein in the diet of those that consumed them. We first hear about this sauce from Greek writers. Later Latin writers call this first sauce a liquamen, not a garum! It seems to have been an everyday product used by the masses in their largely vegetarian foods and not valued by the elite. However by the 1st century AD the entire multi-cultural Mediterranean region had developed an exclusive cuisine based around the idea of fish sauce of multiple varieties and they all functioned as a substitute for salt in daily and special cooking adding that umami kick. How this occurred is very difficult to determine from the literary record but I have a theory…

Read the rest of The fermenting of fish and fish by-products: fish sauces in ancient medicine and cuisine as a pdf.

Comments are closed for this article!